Several people suggested that I write a Beginner’s Guide to Personal Finance, similar to the other guides in my Beginner’s Guide series. But unlike other topics like fitness and languages, the field of personal finance is well-trodden, and there exist mountains of content aimed at beginners, most of which is pretty good.

However, there are several points that I think the popular wisdom about personal finance either gets wrong or doesn’t emphasize enough, so instead of reinventing the wheel, I thought I would post a guide that only includes these.

Note: if you are just getting into personal finance, this isn’t yet the guide for you. I recommend basic overviews that will show you the nuts and bolts of index fund investing, budgeting, and basic frugality, like the r/personalfinance wiki or the book Your Money or Your Life by Vicki Robin.

Table of Contents

Calculate the Value of Your Time

Debt:

Don’t Pay Off More Than The Minimums On Your Student Loans

Use Leverage to Invest in Index Funds

Credit Card and Bank Bonus Churning

Exploit Inefficient Markets Early

Catastrophic Health Plans, HSAs, and Cash

Tax Considerations:

Traditional Is Better Than Roth For Almost Anyone

In a Low-Income Year, Roll Your Old 401K Into a Roth IRA

Tax Loss Harvesting

Calculate the Value of Your Time

This is probably the least unorthodox of all the advice I’m about to give, but for some reason, other personal finance resources fail to emphasize it, despite the fact that knowing what your time is worth at any given moment is the most important concept in personal finance.

Without this knowledge:

- you can’t accept a job, because you don’t know if the salary is worth the amount of hours you’ll be working

- you can’t start a side hustle, because you don’t know if it’s worth your free time for what you might make

- you can’t make decisions about what products to buy, because you might waste more time finding the perfect price than the money you could earn with that time

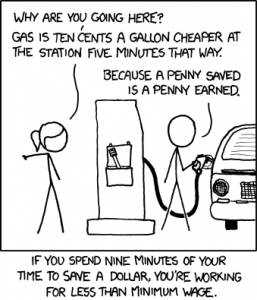

Sure, most people have a rough idea of what their time is worth, but at the margins, there’s plenty of room for errors. Consider the following XKCD comic:

Know anyone like this? Hey, there’s no shame. We’ve all done it at one point or another. Using heuristics to calculate the value of your time on the fly is difficult work, and sometimes our brain gets the better of us. So let’s make it easier. Visit the following calculator: Clearer Thinking — What is your time really worth to you? After you have your value, store it somewhere you can reference it easily, and update it once a year, or whenever your life situation changes substantially. (e.g. you get a new job).

Debt

Many personal finance guides speak only in binaries: debt is bad, and you should get rid of it right away. The real truth is that low-interest debt is good and high-interest debt is bad. If you don’t have any debt, it might actually make sense to borrow money to invest, and you should only pay debt off when you can’t leverage it to make more money for yourself. Thus:

Don’t Pay Off More Than The Minimums On Your Student Loans

When I graduated from college, I constantly overheard chatter from my fellow graduates about how excited they were to get jobs so they could pay off their student loans. From an emotional perspective, I suppose I understand: the feeling that you owe someone money can be soul-crushing. But as soon as you get over this feeling, the soon you’re on the road to making money.

Reason 1: If the interest rate on your student loans is lower than the rate you’d make if you invested the difference, you are losing money by paying them back. I’ll use myself as an example. I graduated college in 2009 with around $30K in debt at just over a 6% average interest rate. I paid only the minimums for my ten year loan term. Instead of paying the rest back, I invested it in index funds. The S&P 500 averaged 12% during that period, meaning I got around a net 6% return on money that was essentially just gifted to me for going to college. Did I get especially lucky? Absolutely! The market could have gone down, and I could have lost money. But the S&P 500 has averaged about 8% on average every year since it’s inception, so I’ll take that bet any day.

Reason 2: By deferring your loans, you are allowing yourself time to max out your tax-advantaged accounts. As soon as you graduate from college, you should set up an IRA, a 401(K), and an HSA (assuming your employer offers the latter two). As of 2021, the yearly contribution limit for these accounts totals to $29,000. If you don’t hit this limit every year, it disappears – you can’t go back in time later in life and contribute for past years. If paying off your loans interferes with your ability to max out these accounts, you shouldn’t pay them off, even if the interest rates are equal to or slightly higher than what the market offers you. P.S. though student loans are the most popular form of low-interest debt, this applies to all debt. Car loans, mortgages, credit card cash advances — every time someone wants to lend you money at less than 6%, you should take it.

Use Leverage to Invest in Index Funds

This is a variation of the above tip: if you’re young, you should be using leverage (debt) to get as much exposure to high-growth investment as possible. Borrowing money to invest it is an inherently risky strategy, but because you have your whole life ahead of you, you have many years to make up the difference if something goes wrong.

The textbook on this theory is Lifecycle Investing, by two Yale professors who studied portfolio management over time. Their main theory is fairly uncontroversial: an individual best minimizes lifetime risk by spreading risk evenly across time. This means that when you’re young and have very little money, you should overexpose yourself to stocks, and when you’re old and have a lot of money, you should transition out of stocks into bonds. Where their strategy differs from conventional advice, however, is that that with very little money, they argue, a 100% exposure to stocks isn’t enough. To truly maintain balanced risks, people at the start of their investing career should actually borrow money to create a de facto 200% exposure to the stock market. An easy way to do this that I myself have implemented is a risk parity strategy using two exchange-traded funds with 3x leverage: UPRO, which triples the S&P500, and TMF, which triples the US Long Term Treasury Index. Leveraged ETFs use debt and swaps to attempt to triple whatever the market does: if the underlying index goes up 1% today, the ETFs goes up (roughly) 3%. If it goes down 1%, the ETF goes down 3%. US Treasury Bonds and the S&P500 have a correlation of approximately zero, which means that a price drop/increase in one does not affect the other. This somewhat protects the portfolio from total bankruptcy should some unforeseen black swan event happens which causes one of the funds to drop more than 33.3% in one day.

Since 1982, this portfolio has massively outperformed the S&P 500. Money invested at that time would have 1030x its value today, compared to a “mere” 50x in the S&P. Of course, from 1955 to 1982 it massively under-performed due to high interest rates, but the assumption is that the Fed will do more in modern times to keep interest rates in check. If they don’t, this strategy is boned. And course, there’s always the chance of total market collapse closing both ETFs, but in that case, pretty much everyone assets would have tanked along with it, so there will be nothing left to do but don our stockpile of N95s and dance around in delight at the downfall of capitalism. YOLO.

If you’re like to read more on this strategy, there’s a thread with many more details on the excellent Bogleheads forum: HEDGEFUNDIE’s excellent adventure.

Disclaimer: this advice is particularly targeted towards younger people. If you’re older than 50, you might want to pump the brakes on some of this and pursue a more conservative investing strategy.

Arbitrage and Side Hustles

Where markets exist, there’s always a way to make money, assuming the return on your time is worth more than the value you calculated above. It’s hard to be specific in this section, because there exist an infinite number of opportunities to leverage your time, knowledge, and or/money to make more money for you, but here are some examples of my side hustles over the years:

Back when online gambling was legal, I took advantage of blackjack and poker bonuses where online casinos paid me between $200 and $500 to play a certain number of hands.

In college, I took old textbooks that were being given away by academic departments and sold them on Amazon. I then started buying textbooks from my classmates and doing the same.

I briefly toyed with affiliate marketing, where I bought Google Adwords to direct searches for ringtones to a landing page I developed to get people to sign up for a ringtone service. I stopped after a few months because it felt unethical.

I made a few hundred bucks with cashback and SwagBucks offers.

Last year, I made $2600 volunteering for the Regeneron monoclonal antibody clinical trial.

Of course, my most lucrative side hustle has been:

Credit Card and Bank Bonus Churning

Credit card issuers often incentivize the opening of new accounts by offering bonuses for the promise of some amount of activity on the card (typically spending $3,000 in three months). They do this because they figure the lifetime value of the customer will far exceed the amount of bonus they give out, if the customer even completes the bonus at all. But you, loyal reader, are not a typical customer. With a modicum of organizational skill and in exchange for a surprisingly low amount of your free time, you can beat the system to the tune of thousands of dollars in cash, flight, and hotel rewards per year.

In 2015, my first year of churning, I opened 14 credit cards, from which I received bonuses to the tune of:

$450 in cash

$715 in statement credits towards travel

50,000 Southwest miles (~$550 in flights)

40,000 Ultimate Rewards points (~$500 in flights)

50,000 Alaska Airlines miles (~$800 in flights)

50,000 American Airlines miles (~$900 in flights)

50,000 British Airways avios (~$650 in flights)

50,000 Citi TYP points (~$500 in flights)

50,000 Delta miles (~$500 in flights)

These were not without costs — in total, I paid $324 in annual credit card fees for access to these cards — but summing it all up, I earned $5241 in credit towards future travel. A liberal estimate of my time spent last year tracking points, applying for cards, and making sure I hit the bonus requirements was about 50 hours. Ergo, I made about $105/hour doing this.

The returns, of course, diminish. There are only a certain amount of credit cards that are worth it to get, and many of them you can only get once in your lifetime, or every few years (hence the term churning, as churners will wait and cycle through opening the same card over and over). In addition, many card issuers have gotten wise as the churning community has grown, and have increased their requirements, or simply denied bonuses entirely.

Bank account bonuses exist as well, and haven’t experienced the same crackdowns as credit cards have. Typically, banks will throw a new customer through a few hoops, like depositing a certain amount and keeping it in the account for a while, using the bank’s debit card a certain number of times, and/or making a few direct deposits into the account. For this, though, you can net $300-$500 in cold hard cash. Finally, to handle the most common objection: no, this doesn’t materially downgrade your credit. It is perfectly legal, and you won’t get banned for having credit cards or something. The finer details of churning are too detailed to explain here, but I can offer two places to learn everything you need to know: Doctor of Credit and the r/churning subreddit.

Exploit Inefficient Markets Early

Whenever you see an opportunity in a market before others do, you have the opportunity for financial gain. I can proffer a few examples from my own life: In 2017, a friend told me that I should look into buying Ethereum. I did a lot of research and really liked what I saw from the developers and the platform. Not only did I think it offered real-world future value, I knew that I was a relatively early investor compared to the general population. I bought and held. Ethereum’s value has increased 7x since.

After the 2020 election, I saw a reddit post about a prediction market called Polymarket that was offering a bet on whether Trump would be inaugurated as president. The market was giving Trump a 17% chance… again, this was after he had lost. Polymarket had only been around for a few months, so I was taking a risk, but I put in $10,000 and walked away with $1400 (after fees) of irrational Trump supporter money the day after Biden was inaugurated.

The common thread between these two examples? Being a first-mover. You’re much more likely to find market inefficiencies when you arrive to a market early.

Catastrophic Health Plans, HSAs, and Cash

There’s no better way to get me on a good rant than bringing up the absolute dysfunctional patchwork of the United States healthcare system. But today, I’ll spare everyone that rant, as there’s always a way to make the best of a bad system. Provided you are healthy and relatively risk-averse, the optimal strategy for the US healthcare system is to:

1. Get high-deductible insurance.

2. Get a Health Savings Account (HSA) and max it out each year.

3. Don’t use your HSA to pay for healthcare. Pay with insurance or cash, whichever offers you a better rate.

4. If you feel like you have a condition that will exceed your deductible in a given year, use only your insurance.

This may sound radical, but it actually harkens back to how insurance was always intended to be used: smoothing risk against a possible catastrophic eventuality. When the Mediterranean traders were insuring their entire ships and cargo against loss in 1700 BC, I think they would be shocked to find our current system of most everyone in the US using their insurance to pay for even routine medical procedures!

To implement this strategy, pick the insurance plan option with the lowest monthly cost, which is almost always a catastrophic plan with an extremely high deductible ($3000-$7000). Then, only touch the plan when its contracted rate for an in-network provider is lower than the cash rate a provider offers (you can verify this using your insurance’s website and a call to the provider).

Every time I need medical care, I call 8-10 providers, ask them for their cash price and availability, and pick whichever one works best. Then, when they ask me what my insurance is, I just lie and say I don’t have insurance (I’ve learned I now have to do this or else they get confused why I’m not using my insurance to pay) and ask if they have a cash discount. In the US, we have ridiculous incentives where the providers bill the insurance for way more than their cash price. If you have high-deductible insurance and your company does not have a discounted contract rate with a provider, you are punished for using it for anything that comes under the deductible limit, because you pay 100% of the inflated insurance price from your provider. A provider recently sent a prescription through my insurance’s pharmacy. The cost was $168. I cancelled it and paid cash for the same medication from a local pharmacy using a GoodRx coupon for $19.

But wouldn’t it make sense to just pay a higher monthly premium for better health insurance? This is where the HSA comes in. Since its inception in 2003, the Health Savings Account has been the best tax-sheltered investment vehicle in the country (at least among those that most people have access to). However, you only get the full benefit if you don’t use it in a slightly off-label way. The HSA is commonly marketed as one-way savings: you divert some of your paycheck to an account and you get to write off taxes on that amount when you use it to pay for healthcare expenses. However, this ignores the far more powerful benefit of the HSA: you can invest that money in the market and withdraw any earnings tax-free as well! Thus, the optimal strategy for the HSA is to:

1. Max out your account every year (as of 2021, the maximum contribution amount is $3600)

2. Invest the money in the market and do not touch it.

3. Keep all your receipts from healthcare expenses during your lifetime.Believe it or not, you can backdate withdrawals, so you can “pay yourself” for expenses you incurred when you were 27, even if you’re withdrawing money at age 60.

4. Once you’re ready to withdraw the money, enjoy withdrawing the entire amount you’ve ever paid on healthcare in your life, totally tax-free.

For more on how to use an HSA optimally, see this HSA article from The Mad Fientist.

Overall, the combination of catastrophic plans, paying cash, and your HSA should save you a bunch of money throughout your healthy life. But some years, you might need to spend $6000 on healthcare. Because you have a high deductible, you’ll end up spending all of that in cash; your insurance won’t help at all. In these years, I recommend switching to using your insurance as a payer when you’re heading towards the deductible limit. You can also save up cash receipts and try to submit them to your insurance later for reimbursement.

Kill Your Emergency Fund

Anyone active in personal finance spaces is familiar with the idea of an “emergency fund”, typically 3-6 months living expenses kept in a high-interest savings account. Yet incredibly, despite being a pervasive force throughout the entire personal finance community, not a single person has been able to make a cogent argument for why anyone should hold that much money back in a low-interest emergency fund instead of using it to invest in the market.

Nerdwallet says that the reason to keep an emergency fund is so you can pay for “Unforeseen medical expenses, home-appliance repair or replacement, major car fixes, and unemployment”.

The truth is that none of these are emergencies. Medical expenses, replacing home appliances, and fixing cars can all be done with a credit card. If you’re unemployed, you can start selling off your equities to pay for your living costs.

If someone can name just one real emergency that would require them to have completely liquid access to tens of thousands of dollars, and could not be paid for by a credit card, I’ll change my mind. Until then, kill your emergency fund.

Tax Considerations

The US tax system is ridiculously complex, which is bad news for everyone. But those who know ins and outs can take advantage of benefits that others miss out on. This isn’t just for rich people, either. here are three tips that you might otherwise be paying an accountant to tell you:

Traditional is Better than Roth for Almost Anyone

Roth IRAs and 401Ks have gained much prominence recently, especially with advice aimed towards younger investors. The benefits of Roth accounts look great on paper compared to Traditional accounts:

- You pay tax on money going in, and can withdraw money tax-free, making it seemingly attractive for low earners.

- You can withdraw your base at any time without penalty.

- No required minimum distributions.

The common mantra repeated around Roth accounts is “if your tax bracket will be lower now than it is in retirement, you should always contribute to a Roth”. It’s amazing how pervasive this saying is, considering that it isn’t true. I can see why people make the mistake, though. It’s easy to say “I’m in the 12% tax bracket now, surely I’ll be higher than that once I retire!”

Not so fast. The mental error here is not considering that our income tax structure is progressive and follows the “last dollar principle”. The money you invest into a retirement account is always the last dollar you earned, while the money you withdraw from that account in retirement is the first dollar you earn.

Let’s take an example, a recent college grad making $35,000 a year in the 12% tax bracket. This young buck heard that he could pay the 12% now and then pay no tax upon retirement when he withdraws the money. For four years, he contributes $5,000 a year, for a total of $20,000.

For each of these years, he paid an additional 12% in tax, for a total of $2400.

Let’s fast forward about 50 years and assume that our tax brackets stay exactly the same:

On the first $12,400, he pays 0% tax due to the standard deduction.

On $12,400-$20,000, he pays 12% tax, for a total tax bill of $912.

And that’s not all: the $2400 in paid tax could have been invested in a brokerage account over those 50 years and continued to gain interest, instead of paying it to Uncle Sam right away.

After all that, the vaunted Roth IRA actually cost our investor more upfront than it took to deduct, and this is all using an example of someone fresh out of college making very little money.

In almost all situations where you would think of using a Roth IRA, a traditional IRA is the better play.

For more on this, see The Great Roth Controversy from Go Curry Cracker.

In a Low-Income Year, Roll Your Old 401K Into a Roth IRA

If you’ve left a job and have an old 401K sitting around, you can roll it into a Roth IRA. Not only does this simplify your life by minimizing your number of open accounts, it also lets you get around annual Roth contribution limits, which means you’ll be able to access that money anytime you need it, penalty-free. The caveat is that you’ll have to pay taxes on the total amount you roll over, so it’s important you do this in a low-income year, one where you’re sure you’ll be in a far lower tax bracket than you would in retirement.

Tax Loss Harvesting

You can save a decent amount of money by using a roboinvestor like Wealthfront or Betterment, which perform automatic portfolio rebalancing and tax loss harvesting. Under the tax loss harvesting scheme, these investment sites use an algorithm that automatically buys and sells certain securities to make sure you receive tax losses that can be written off as an IRS capital loss. It’s likely that this could improve the performance of your underlying investments by ~0.75%, which is far more than the fees each platform charges. Note that this can only be done with taxable accounts, due to the frequent trading that occurs within these platforms.